Jessamine County EMS and E911 have joined with PulsePoint to help increase the survival rates of cardiac arrest victims. This is a free, life-saving smartphone app that alerts everyday citizens when CPR is needed for patients in cardiac arrest.

What is PulsePoint?

- Alerts CPR-trained bystanders to someone nearby having a sudden cardiac arrest that may require CPR. CPR alerts are only shared if the event occurs in a public place (the app is not activated for residential addresses).

- Shares alerts as local public safety communications center dispatch local fire and EMS resources.

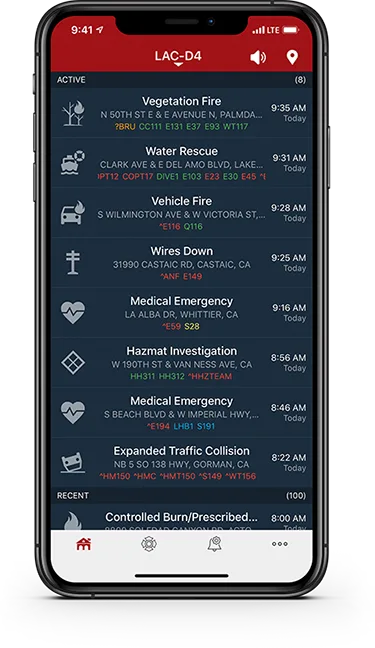

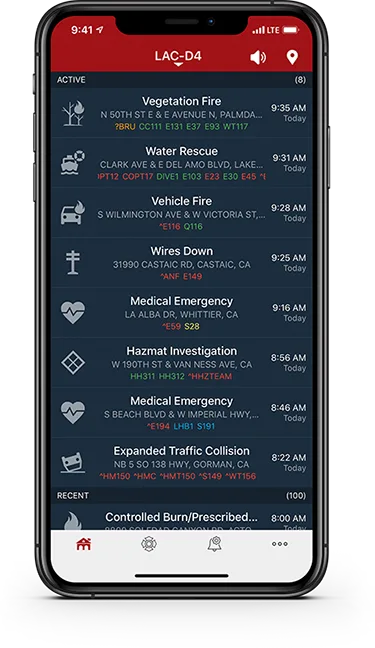

- Provides real-time feed of fire and EMS emergency calls, offering a unique opportunity for civic engagement and transparency.

Active Call Feed

Active Call Feed

Frequently Asked Questions

How does the app work?

The PulsePoint app, developed by the PulsePoint Foundation, integrates a mobile application, a cloud-based middle tier web service, and a dispatch system interface to aid in life-saving efforts. Available for both iOS and Android devices, it allows users to select their preferred emergency agencies within a unified application. Hosted on Amazon EC2, the middle tier ensures secure and encrypted communication between users’ devices and emergency communication centers through HTTPS with SSL/TLS. The core of the system, the PulsePoint API, enables seamless interaction between the emergency centers’ Computer-Aided Dispatch (CAD) systems and the app, alerting CPR-trained bystanders to nearby cardiac emergencies and potentially increasing survival rates for victims of sudden cardiac arrest.

HIPAA and other privacy concerns?

The PulsePoint app adheres to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) by safeguarding the privacy of health information. It only shares the location (address or business name) of a ‘CPR Needed’ event in public spaces, without disclosing any personally identifiable information like names, birth dates, or Social Security Numbers. To ensure legal compliance and assist agencies with dispatch liability and HIPAA concerns, PulsePoint has partnered with Page, Wolfberg & Wirth, LLC (PWW), a reputable EMS law firm.

PulsePoint is a Location-Based Service (LBS) that leverages your mobile device’s geographical position to show your location in relation to nearby incidents. This feature is optional and requires user consent to activate. If you opt into CPR/AED notifications, the app temporarily stores your device’s current location to potentially direct you to nearby emergencies, without keeping any movement history or identifying you personally.

How is it verified that CPR/AED notification subscribers are trained and qualified?

CPR (Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation) has become highly accessible and simple to learn, with training available through informal means such as community events, group sessions, home DVDs, or online videos, often without formal certification. Similarly, Automated External Defibrillators (AEDs) are designed for ease of use without the need for prior training. As a result, there’s no practical way or necessity to verify formal training for individuals willing to volunteer in providing CPR or using an AED to assist others.

How can misuse of CPR/AED alerts for theft or exploitation of cardiac arrest victims be prevented?

The activation of the app requires an initial call to the local emergency number (e.g., 911), initiating a standard public safety response. This process ensures that the victim is likely not alone when CPR/AED notifications are dispatched. Moreover, the app is specifically designed to activate for incidents occurring in public places, not private residences, increasing the chances that others will be around. Additionally, since notifications are sent only to devices in the immediate vicinity of the victim, the opportunity for a “Bad Samaritan” to exploit the situation is significantly minimized, as they would need to be precisely in the right place at the right moment to receive the alert.

Could the app attract too many bystanders to an emergency scene?

Currently, only about one-third of sudden cardiac arrest victims receive CPR from bystanders, and public access to Automated External Defibrillators (AEDs) is utilized in less than 3% of cases when they are needed and available. This indicates a significant shortfall in bystander intervention during such emergencies. The primary aim of the app is to increase the number of bystanders who can perform these lifesaving actions. Should the app significantly boost bystander response rates in the future, it would be considered a major success, potentially allowing for a reduction in the notification radius to manage the increased volunteer presence effectively.

What is the notification radius for CPR/AED events?

The app is designed to alert individuals who are essentially within walking distance of an emergency event. However, the specific distance covered by the notification radius can be adjusted according to the preferences of each participating agency. In areas with high population densities, a smaller radius is typically set to target nearby responders efficiently. Conversely, in rural regions where government emergency response times may be longer, agencies might opt for a broader notification area to ensure sufficient coverage and increase the chances of timely assistance.

Can I be sued for voluntarily assisting a victim in distress?

The Good Samaritan Law is designed to offer legal protection to individuals who voluntarily assist victims during a medical emergency, primarily aimed at the general public and assuming the absence of medically trained personnel. This law shields Good Samaritans, who lack medical training, from liability for injuries or death that may occur while attempting to help a victim in an emergency, provided their actions are with good intentions and within their capabilities. Protection under Good Samaritan laws applies as long as the individual acts as a reasonable and prudent person would under the given circumstances, without seeking compensation. Since the specifics of these laws vary by state and this overview does not encompass global legislation, it’s important to acquaint yourself with the relevant laws or acts in your area. An example of typical language used in these laws is:

“…a person, who, in good faith, lends emergency care or assistance without compensation at the place of an emergency or accident, and who was acting as a reasonable and prudent person would have acted under the circumstances present at the scene at the time the services were rendered, shall not be liable for any civil damages for acts or omissions performed in good faith.”

Is it possible for the app to send a CPR/AED notification when CPR isn't necessary?

Yes, there is a possibility of incorrect assessments over the telephone by dispatchers, who rely on observations from untrained callers. Situations like a grand mal seizure, excessive alcohol consumption, or extremely high blood sugar levels might be misinterpreted as cardiac arrest. In such cases, attempting CPR on an individual not in cardiac arrest could lead to them moaning or trying to push the responder away, indicating they are not in need of CPR. Additionally, an Automated External Defibrillator (AED) is designed not to administer a shock if it detects any effective heartbeat, further safeguarding against inappropriate use on individuals who do not require it.

How does PulsePoint identify a location as public?

The application determines if an incident location is public by initially consulting with the originating emergency agency, which serves as the most reliable source for such local information. This is achieved by examining the “Public” field in the incident’s record, provided through the agency’s interface (API). Agencies have the capability to mark this field as True for public locations, based on assessments from their computer-aided dispatch (CAD) system, GIS layers, local databases, etc. For instance, if the CAD system identifies an incident location as a local park, it will communicate to PulsePoint via the API that the location should be considered public. Conversely, if the incident is at an apartment building, the agency can set the “Public” field to False, indicating a private location. In cases where the “Public” field is not specified, PulsePoint resorts to querying public data sources, such as the Residential/Commercial Indicator (RDI) from the USPS (utilizing the USPS address validation API from SmartyStreets) and the Google Places API, to make an informed decision on the public or private nature of the location.